Culture and reverse culture shock represent a part of life’s natural challenges where a discrepancy between your known world is coupled with an intrinsic need for identification, placed into an unknown world (Lora Engels, 2023).

–> Read 10 minutes

I have decided to dedicate my first article on this blog to culture shock. Not because it is the most interesting or the most challenging, nor the most present in my day-to-day life. Yet, it is an omnipresent phenomenon I encounter, that perhaps, greets you too.

Also, it is an occurrence of an experience that I will return my attention to during the course of this blog. It hits you no matter the level of preparation or instrumentalization*, in my opinion. It is a topic that encounters multiple classifications, concerning the types and motives of travelers. Moreover, it is transferred to the concept of loss, bereavement, and attachment (Bochner, Furnham, 1986).

Why are researchers interested in this type of shock?

So as to identify and eliminate risk factors and possible stern consequences.

With that being said, today the goal is to shed light on a few tricks that have helped me in the past.

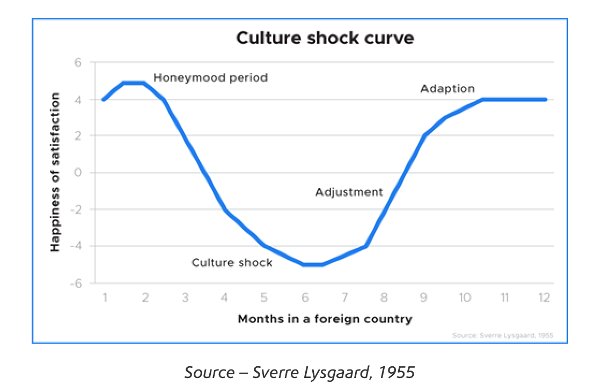

Anthropologist Kalervo Oberg (1954) coined the idea around the phenomenon plus idealized the corresponding phase model with its four stages of excitement – irritation – adjustment – adaptation. Let that sink in and read it again; excitement – irritation – adjustment – adaptation. Sounds like something you have overcome?

Culture shock is apparent in our dating life when facing language barriers, by moving countries, visiting new nations, tasting new cuisines, and overall by being exposed to a new level of awareness within a foreign and new environment. It’s the transition where one may (un)consciously become aware of one’s attachment to certain foods, behaviors, environments, and more.

The concept of culture shock has been attributed to something normal in our Westernized and globalized world. It has become a concept of a concept. A privilege of “the normal” as you may categorize it. Why do I write privilege? Because it is an opportunity (self-made or handed) to be exposed to a new experience. Hereby, we associate migrant and traveler groups with diverse motives, as well as expats and digital nomads moving abroad, or students following an internship/voluntary work. Next, other individuals and groups fall prey to this phenomenon like refugees, diplomats, missionaries, and more. Those are instances where desire, (net)work, and opportunity meet.

The mentioned four stages have been widely adopted to make people understand that what they are going through is normal—to a certain degree. The symptoms that are experienced are attributed to a reason. That we must remember to respect foreign customs and cultures despite our belief system. Let’s go through them, one by one, and see if you can relate.

(1) The so-called honeymoon stage is the part where you are freshly exposed to the new idea of moving from, let’s say, Frankfurt to Rio de Janeiro. Maybe you have already arrived at your destination. Everything seems exciting; you absorb every little detail around you with curiosity, expectation, and the need to touch and try everything (here, encounters of respect are fetching a new lens).

(2) Next, some time has passed, and you realize things are different from what you know and you might start to feel uncomfortable. Foreign circumstances and customs have become part of your new life, so you feel the need to identify yourself. Irritation and frustration kick in, or in other words, the beloved culture shock phase spreads to every cell. This takes on the form of homesickness or literal illness due to the newly exposed germs and food, sadness, or boredom. Here, many are giving up and may develop a complaining or negative attitude. In severe cases, the new environment, role changes, or role disputes may impact your mental and physical state drastically. When stress feels too overpowering, you should reach out to a professional, family, or someone who has gone through the same. This state shouldn’t persist longer than two months**.

(3) You may enter the adjustment phase when you have decided to stay in midst of the new culture. It becomes easier, you figure out which grocery shop you prefer, where you get your toiletries from, and have perhaps already adapted to the traffic or public transport system. This means, you feel okay and ARE okay in your environment. You feel you can cope little challenges with more ease now.

(4) Ultimately, with time, you enter the adaptation segment. Maybe never fully, but eventually you start the road of integration and acceptance. Further, it takes a necessary sense of instrumentalism to fully accept and adapt.

This curve is very unique to anyone. You may have relapses and find yourself in adaptation back to frustration. From adaptation to eventually returning home and finding yourself in the so-called reverse culture shock. Everything feels weird again, saddening, and illusionary. Your mind and cells had adapted to a new reality, and they needed to overcome so much. So much stress. Suddenly, you are back in your old reality. It feels strange. And it takes time to recover, to integrate. Remember, this curve is not a linear one. Give it time without the need to judge your process.

What has helped me during my move to a new life in Cambodia at the age of 18:

- Keep expectations low. From the start, try not to think about the country and culture too much, and don’t over-research, so that your expectations aren’t set and won’t be disappointed. So to speak, keep it realistic by allowing the new experience to form itself. “Realistic expectations about what will be encountered are the most important factors in adaptation. The closer the sojourners’ expectations about all aspects of their new life and job (social, economic, personal) approximate to reality, the happier they will be and the easier the adjustment.” (Furnham, 2019)

- Create your own space. Take a few things that make you feel comfortable i.e., home. This is especially essential in the beginning because you won’t directly know where to purchase certain items from (e.g., candle lights, a painting, photographs, jewelry, a few snacks, your pillow)

- Find a space to chase your hobby. Don’t get intimidated, continue doing what you love. This helps you to feel confident in your new environment as well.

- Remember why you are there in the first place. Make those extra calls with friends and family, watch inspirational videos, and reassure yourself of the mission you wanted to embark on. Your Locus of Control is the driver in calculating your level of adaptation and becomes the ultimate judge of your experience.

- Keep yourself physically active and find some communal activities. Making connections might not be your first plan of action, yet keep your body moving, let the dopamine kick in, and allow any reset to happen.

To sum up, we should pay more attention to culture shock so to acknowledge and process our environment actively and, hence, optimize our awareness of daily functions.

*A theory of knowledge and view related to pragmatism with ideas focusing on its pragmatic value “In this view, the value of an idea, concept, or judgment lies in its ability to explain, predict, and control one’s concrete functional interactions with the experienced world” (APA dictionary)

**Homesick most and all of the time, sad and anxious most and all of the time, irritable and depressed, tensed and under pressure most and all of the time, feeling out-of-control for a consistent period, experience changes in sleeping, appetite, sadness most and all of the time

–> If you are feeling these symptoms, reach out to the corresponding mental health helpline in your country of choice.

Relevant research looking further into the topic

- Of migration

Furnham, A. (2019) Culture Shock: A Review of the Literature for Practitioners. Psychology. 10: 1832-1855.

- On stress and adaptation

Demes, K. Geeraert, N. King., L. (ed.) (2015) The Highs and Lows of a Cultural Transition: A Longitudinal Analysis of Sojourner Stress and Adaptation Across 50 Countries. American Psychological Association, 109(2): 316.337.

Winkelman, M. (1994). Cultural Shock and Adaptation. Journal of Counseling & Development. 73: 121-126.

- Rewiring your unconscious with Vipassana mediation by Buddha & S. N. Goenka– What is it? My experience (body scan, practice not to react to distractions, Noble silence)Mindfulness Meditation: A Technique to alleviate your suffering and cultivate pure compassion For Stress Reduction and Improved Well-Being Not without a reason you find inspirational speakers and authors like Eckart Tolle, Sadhguru, and of course S. N. Goenka, spreading the word about this mindful meditation technique, explored and developed by Buddha Siddhartha Gautama more than… Read more: Rewiring your unconscious with Vipassana mediation by Buddha & S. N. Goenka– What is it? My experience (body scan, practice not to react to distractions, Noble silence)

- Why should we pay more attention to culture shock?Culture and reverse culture shock represent a part of life’s natural challenges where a discrepancy between your known world is coupled with an intrinsic need for identification, placed into an unknown world (Lora Engels, 2023). –> Read 10 minutes I have decided to dedicate my first article on this blog to culture shock. Not because… Read more: Why should we pay more attention to culture shock?